Extreme Provocation & Justifiable Use of Force in Ghana’s Criminal Jurisprudence

ABSTRACT

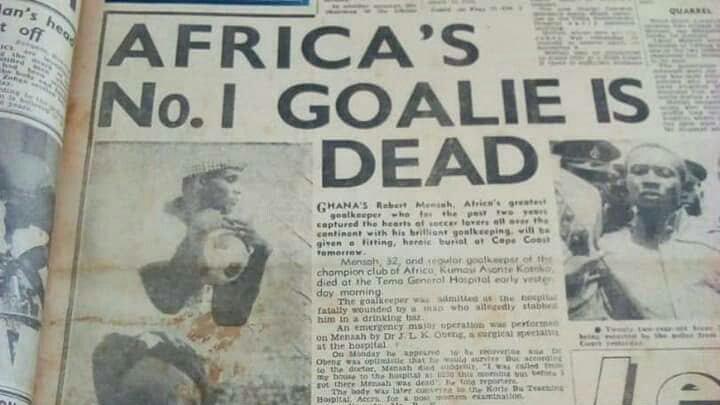

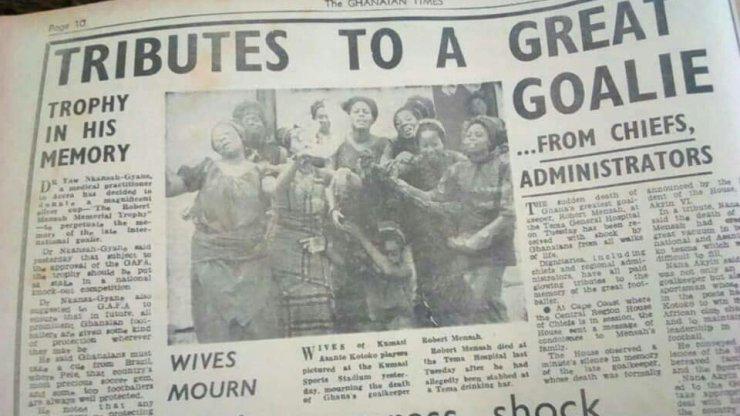

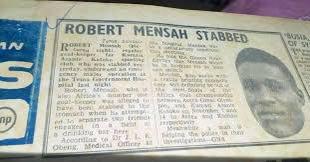

It has been fifty (50) years since Melfa v The Republic was decided. In the cited case, the Court of Appeal dismissed a challenge against the conviction of the accused for the manslaughter of Robert Mensah, “an international football star;” but allowed the appeal against the “harsh” sentence. In doing so, Sowah J.A. (as he then was), stressed that the deceased was the aggressor in the scuffle and the trial judge ought to have considered that before imposing a harsh sentence. Four years imprisonment was substituted for an eight year-term imposed by the trial court and the incident which courted national outrage due to the deceased’s high-profile got closure. Half a century on, the question as regards the propriety of the decision continues to divide students of criminal law and even legal practitioners. To what extent did the bench consider all defenses available to or pleaded by the appellant? This paper attempts an investigation into the jurisprudential development of the defenses of extreme provocation and justifiable use of force; (self-defense)—which were available to the appellant; the extent of these defenses and the limitations of each. The paper also relies on statute and case law to illustrate and determine the similarities and divergence between these defenses. What should inform a court’s decision to accept one over the other—for one exonerates the accused while the other only goes as to reduce his liability. How do these defenses reflect in the Criminal Offenses Act, 1960 (Act 29); and to what extent did Sowah J.A. and his colleagues accurately apply them in the case under review? By examining these defenses, the writer argues that their Lordships in Melfa, with the greatest of respect, misapplied the law when they held remitting the sentence but did not allow the appeal to the conviction on the whole.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Special Thanks to Basit Fuseini ESQ, Frederick Agaaya Adongo, Benjamin Alpha Aidoo, Moses Ekow Andoh, Joel Afari-Acquah, Kabu Nartey and Charles Okyere for their arduous and indispensable roles in bringing this paper to life.

Tracing the Nuances in Extreme Provocation & Justifiable Use of Force in Ghana’s Criminal Jurisprudence: A Golden Jubilee Tribute to Melfa v The Republic

INTRODUCTION

The fundamental principle of criminal law is that no person should be convicted of an act or omission which was not criminalized at the time the said act or omission took place. This indispensable part of the law is expressed in the maxim nullum crimen sine praevia lege. The Constitution, 1992 captures this maxim in Article 19 (5) and (11). These provisions reflect the principle of legality which seeks to prevent the courts from applying criminal statutes retroactively or imposing punishments for non-existent crimes. Prosecutors can thus only succeed in proving criminal liability for offenses contained in a duly enacted law. How then does the criminal process determine an accused’s criminal liability? The prosecution proves the Mens Rea or the mental element of the crime, with a concurrent act or omission, known as the Actus Reus, and in the absence of a valid defense, the accused is likely to be convicted.

Thus, although the law may proscribe the killing of a fellow man, a valid defense, say the carrying out of a lawful order or an element of necessity may, completely or partially, discharge an accused of liability in the killing. It was on one of such grounds (provocation) that the then accused in the killing of Robert Mensah was convicted on the diminished liability of manslaughter instead of murder and his appeal against conviction dismissed at the Court of Appeal.

In the ensuing paragraphs, the paper will focus on two key defenses to homicide—extreme provocation and justifiable use of force, specifically, self-defense. The two defenses admit that the accused killed the deceased but contend that his liability be reduced or discharged due to specific circumstances which resulted in the killing. In the discussion, the writer guides the reader through a critique of their Lordships’ conclusion to dismiss the appellant’s challenge to his conviction in the trial court.

PROVOCATION AS A DEFENSE TO MURDER

Provocation, in simple English is the deliberate act of making someone angry. As a criminal defense, (extreme) provocation means much more; with its principal characteristic being that it is only available to a murder charge. Simply put, the defense argues that the deceased’s behaviour created extenuating circumstances to mitigate the accused’s liability. If the jury accepts the defense, the accused is not convicted on murder with which he was charged but is convicted on the reduced liability of manslaughter. In homicide trials, extreme provocation could be the most important deciding factor in construing a confrontational killing of another as either murder or manslaughter. The Criminal Offenses Act, 1960 (Act 29) treats the two crimes.

The Act defines murder as intentionally causing the death of another by an unlawful harm, unless the murder is reduced to manslaughter by reason of an extreme provocation, or any other matter of partial excuse, as is mentioned in Section 52.

It defines manslaughter as: causing the death of another by an unlawful harm…but if the harm causing the death is caused by negligence, that person has not committed manslaughter unless the negligence amounts to a reckless disregard for human life.

The two definitions give rise to two forms of manslaughter; voluntary manslaughter and involuntary manslaughter. The definition of murder also creates the offense of voluntary manslaughter, the mens-rea to cause death; intent, being present but the offense is mitigated due to extenuating circumstances stated in Section 52. In the definition of manslaughter in Section 51, the mens rea of intent to kill is absent , thus, the unlawful harm which results in fatality—as well as negligence, which amounts to a reckless disregard for human life, [emphasis mine] define involuntary manslaughter. The suffix means mere medical negligence, for instance, may not be enough for a prosecutor to discharge the burden of proof beyond reasonable doubt. Reckless driving may suffice. This paper partly focuses on voluntary manslaughter, supra. This would have been murder except for the extenuating circumstances permitted by the Act—which include extreme provocation leading to loss of self-control and loss of self-control simplicita from a fear of imminent death or bodily harm which caused the accused to go in excess of the harm he was justified to cause.

The preceding paragraphs underscore a salient principle on the law of extreme provocation and loss of self-control which is but a partial defense to murder. It does not absolve the accused entirely of the homicide but reduces liability as mentioned above. At common law, all unlawful homicides which are not murder are manslaughter. This overview of the defense of extreme provocation sets the stage for a walk through its development by judicial action and relevant statute.

Lord Devlin, in R v. Duffy gave provocation its classic definition as:

“some act, or series of acts, done by the dead man to the accused, which would cause in any reasonable man, and actually causes in the accused, a sudden and temporary loss of self-control, rendering the accused so subject to passion as to make him or her for the moment, not a master of his mind.”

Lord Devlin

From Lord Devlin’s definition, the elements needed for a defense of provocation to succeed can be divided into four. Firstly, there should be a sufficient provocation, secondly, there should be a sudden and temporary loss of self-control, thirdly, the accused must prove that the immediate provocative act caused his loss of self-control which triggered his instantaneous reaction and lastly, the defendant’s reaction or response to the provocative act should be equivalent to that of a reasonable man in his community who is in his position.

A careful scrutiny of the authorities will demystify these elements. Firstly, in Duffy, the accused was charged with murder. She had killed her husband with a hatchet while he slept. In her defense, she contended that the deceased subjected her to regular violent abuse and on the night in question, a quarrel ensued after which the deceased slept and she fatally attacked him. The Court of Appeal accepted the direction Lord Devlin gave to the jury and dismissed her appeal against a conviction for murder. This case illustrates sufficient provocation, but based on the facts, the second, third and fourth elements cannot be supported. The fracas of the evening had ended which means there was no sudden and temporary loss of self-control, and there was no immediate provocative act which would be the catalyst. The requirement for a reasonable man in her position, therefore, does not arise.

In DPP v. Camplin, the power of self-control was stressed as an important factor in determining whether the defense of provocation should succeed. The respondent, who was 15 at the time of the crime, was convicted of murder after he struck and killed a middle-aged man for forcefully having sex with him and then laughing at him. The conviction on murder was overturned and replaced with manslaughter, whereupon, the prosecution appealed to the House of Lords which dismissed the appeal. Lord Diplock noted that contrary to the direction of the trial judge, the jury ought to have considered the age of the respondent in determining whether he was sufficiently provoked and thus, lost the power of self-control.

Provocation and other partial defenses in Act 29

These common law elements are highly represented in Act 29. Section 52 of the Act provides that the benefit of provocation will be available to an accused if they prove they were deprived of the power of self-control by a provocation given by the deceased. It should be noted that both England and Ghana have codified what can constitute extreme provocation. It is not left to the judge’s discretion. Section 53 of Act 29 gives the specific acts which constitute sufficient provocation as to deny one the power of self-control. It provides that

The following matters may amount to extreme provocation to one person to cause the death of another person namely

(a) an unlawful assault and battery committed upon the accused person by the other person, either in an unlawful fight or otherwise, which is of such a kind, either in respect of its violence or by reason of accompanying words, gestures, or other circumstances of insult or aggravation, as to be likely to deprive a person, being of ordinary character and being in the circumstances in which the accused person was, of the power of self-control.

(b) the assumption by the other person, at the commencement of an unlawful fight, of an attitude manifesting an intention of instantly attacking the accused person with deadly or dangerous means or in a deadly manner.

(c) an act of adultery committed in the view of the accused person with or by his wife or her husband, or the crime of unnatural carnal knowledge committed in his or her view upon his or her wife, husband, or child; and

(d) a violent assault and battery committed in the view or presence of the accused person upon his or her wife, husband, child, or parent, or upon any other person being in the presence and in the care or charge of the accused person

Two cases illustrate when the defense of provocation will succeed as a partial defense to a charge of murder. In Kontor v. The Republic, the appellant’s conviction for murder was substituted for manslaughter on appeal. As provided by Section 52 (b), a partial defense may be available to an accused if:

“…he was justified in causing some harm to the other person, and, in causing harm in excess of the harm which he was justified in causing, he acted from such terror of immediate death or grievous harm as in fact deprived him for the time being of the power of self-control” [emphasis mine].

The Court of Appeal, speaking through Abban J.A., in allowing the appeal, specifically, stressed on the absence of the intent to kill. The court explained that, the conviction on murder cannot be supported in the absence of the said intent.

Abban J.A. remarked:

“in the case of murder there should be proof of an intention to kill whilst in the case of manslaughter such an intent is absent…if they (the jury) found that the intent to kill was absent, then they should in the circumstances consider a verdict of manslaughter.”

The facts were that the accused and deceased were cousins and only engaged in the fatal brawl over a minor misunderstanding. The two had even shared a meal after an earlier quarrel. In the fatal fight, the deceased was the aggressor and he was also bigger in stature. In support of the requirement of a sudden and temporary loss of self-control, Abban J.A. quoted a statement from second prosecution witness who he described as a vital witness. The witness recounted what the appellant said after striking his cousin as: “Kofi, you have made me do serious (or grave) wrong,”—an expression of immediate remorse after regaining control of his mind. All the elements needed to sustain the defense were thus, discharged.

In Zinitege v. The Republic, the appellant struck the deceased, his nephew, with a stick on the head after the latter ambushed and attacked him. There was a record of bad blood between the two and they were previously separated from fighting at a drinking bar hours prior. The deceased was stated as the aggressor in these recorded scuffles. In replacing the conviction on murder with the lesser crime of manslaughter, the Court of Appeal, per Brobbey J.A. explained:

“in the instant case, the three successive attacks must have led the appellant so to lose his self-control as to resort to the one and only move he took which turned out unfortunately to be fatal.”

The two authorities are leading cases under the law of provocation and loss of self-control in Ghana and underscore the need for loss of the power of self-control as the celebrated Lord Devlin elucidated in the Duffy case. It is, therefore, an unobjectionable fact that the defense of provocation cannot be sustained unless there is proof of loss of self-control. In that moment, the accused is believed to have lost it all by the extreme provocation given by the deceased. Not every inflammatory behaviour by a provocateur would, however, entitle an accused to the benefit of the defense of extreme provocation where the accused responded in a deadly manner and did in fact, kill the provocateur. Even where the provocation given constituted sufficient extreme provocation under Act 29, the law limits the circumstances under which an accused may successfully plead the mitigating defense—this circumstances, for expediency, are reviewed herein.

Limitations of Provocation

One of the earliest cases to mention the defense of extreme provocation is R v. Mawgridge where the requirement for loss of self-control was set out. The court was emphatic that insults and mere words cannot legally provoke one into killing another.

Per Holt CJ,

“no words of reproach or infamy, are sufficient to provoke another to such a degree of anger as to strike, or assault the provoking party with a sword, or to throw a bottle at him, or to strike him with any other weapon that may kill him; [so] if the person provoking be thereby killed, it is murder”

In Section 53 of Act 29, the words of Holt CJ are reflected. As quoted above, the Section accepts words of insult and infamy as constituting extreme provocation only if they are accompanied with an unlawful assault and battery. The limitations proper are captured in Section 54 of the Act and are not new to principle laid down by Devlin. The basic requirement which summarizes the defense is that the accused’s violent reaction, though unlawful, was equivalent to that of a reasonable man who has been provoked into losing the power of self-control and is in the heat of passion. The absence of loss of self-control, acting directly from a previous intent to cause harm to the deceased, lapse of time; which defeats the heat of the moment requirement and in other cases, acting in excess of what a reasonable man would do, form the basis of the exclusion to the benefit of Provocation in Ghana as expressed in Act 29.

The two most relevant variables which are fatal to the defense of provocation deduced from Section 54 of Act 29 are lapse of time—which proves the accused did not act in the heat of the moment but had time to cool off and regain control of his mind, thus, did not lose the power of self-control when he reacted—and the degree of his reaction, in respect either of the instrument or means used or of the cruel or other manner in which it was used, in which no ordinary person would, under the circumstances, have been likely to act.

The Duffy case, specifically, illustrates the limitation of lapse of time. The appellant had cooled off after the fight with her husband and only returned to attack him when he was asleep. Time had therefore lapsed and she thus, lost the key requirement to have acted in the heat of the moment, being deprived of the power of self-control from an extreme provocation from the deceased. Her killing of her husband, was, thus, premeditated; making it outright murder. It is thus, a settled principle that when time lapses on an extreme provocation, no person shall be entitled to kill, or excused, or partly excused for killing the provocateur due to the said extreme provocation —one must have acted only in the heat of the moment.

Similarly, an accused loses the benefit of the defense of provocation where he reacted to the extreme provocation in a manner that exceeds what a reasonable person in his position would do. The weapon used, the manner in which it was used to strike the deceased—which could be evidenced by number of strikes, should be of relevance to any jury considering the defense. It was based on these requirements that the jury rejected the accused’s plea of provocation in Larti v. The State. The Supreme Court dismissed the appeal of the convict. The relevant facts are that after an alleged provocation by the deceased, where appellant averred he was hit by a stick, he returned the blow by inflicting twenty-four machete wounds on the deceased. Bruce-Lyle J.S.C., in delivering the judgment of the court, applied Section 54 (d), holding that the nature of the response did not match the alleged provocation.

Another circumstance under which the defense of provocation would not suffice is where the accused was merely angry and struck the deceased out of a loss of temper instead of loss of self-control owing to an extreme provocation. Mere anger is not tantamount to loss of self-control from an extreme provocation as to make one not a master of their mind. This position is illustrated in the leading case of R v. Parent where the court held that intense anger alone is not sufficient to reduce murder to manslaughter—it may play a role in determining sufficient provocation but is not an independent defense. In Acott supra, Lord Steyn, quoting Rougier J, with approval, indicated that

“It is not enough that the evidence should merely indicate that the defendant had lost his temper, possibly as a result of some unidentified words or actions, for people occasionally work themselves into a fury and erupt with no external provocation at all.”

How fair are the requirements of this defense?

What some jurists have said

The jurisprudential discussions advanced by feminist jurists are notorious in all critiques of the defense of provocation; the central argument being that it is biased in favour of men and greatly disadvantages women. “The defense does little to properly consider the extreme provocation under which some accused women acted in the homicidal attack on their violent abusive husbands” , writes Elizabeth Sheehy. The Duffy case, on which most part of the current nature of the defense sits, is relevant here. The requirement for the accused to have acted in the heat of passion fails to recognize the relative physical strengths and natural build of a woman against a man . Sheehy further argues that men are more disposed to act instantaneously when extremely provoked whereas women are more tolerable and more disposed to react to provocation after the heat. In the present writer’s opinion, these are valid concerns which the element of acting under an instantaneous loss of self-control fails to consider.

The rejection of anger as a defense has also courted denouncement. And rightly, so. The matter should be given better judicial or legislative development. Trotter, (2002) writes that

“Whether anger is capable of negating the intent for murder may be a question that is susceptible to expert opinion. Therefore, if the Court’s holding rests on the notion that intent cannot be negated by anger, however intense, there ought to have been a proper empirical foundation to support that conclusion…”

The killer of Robert Mensah was convicted of manslaughter instead of murder because in the jury’s opinion, the celebrated goalkeeper extremely provoked the appellant by launching multiple attacks on him. The jury considered all the events of the night and concluded that despite being initially innocent, the appellant used excess force to stop the provocation and attack on him by Mensah. The courts refused the plea of self-defense from the killer which would have made him walk out of court as a free man. This writer disagrees with the jury and the Court of Appeal for reasons now set out.

JUSTIFIABLE USE OF FORCE

At the heart of the defense of justifiable use of force is that the accused had the right to defend himself with as much force as was reasonably necessary in the circumstance, even if it leads to the attacker’s death. It is a complete defense and leads to the acquittal and discharge of the accused unlike extreme provocation which is only a partial defense. The recent decision of Dobbs v. Jackson has underscored the need to trace any claim of a right to the Constitution. In Ghana, the right to self-defense is provided for in Article 13 of the Constitution, 1992. It provides as follows:

A person shall not be held to have deprived another person of his life in contravention of clause (1) of this article if that other person dies as the result of a lawful act of war or if that other person dies as the result of the use of force to such an extent as is reasonably justifiable in the particular circumstances

(a) For the defense of any person from violence or for the defense of property

The right to self-defense is further stressed in Section 37 of Act 29.

Section 37—Use of Force for Prevention of or Defence against Criminal offense

For the prevention of, or for the defence of himself or any other person against any crime…a person may justify any force or harm which is reasonably necessary extending in case of extreme necessity, even to killing.

The effect of Article 13 of the Constitution and Section 37 of Act 29 is that where the facts show the accused used force or harm which was necessary in the circumstance, the said harm is not unlawful and he consequently, committed no crime. The accused, thus argues quod est necessarium est licitum and the court is to assess the entire circumstance to determine if he should succeed.

An inseverable component of the defense of justifiable use of force as to constitute self-defense is necessity. Necessity itself is a stand-alone defense at common law but in Act 29, it is not treated as an independent defense but as a vital component in establishing defenses such as justifiable use of force which is under discussion herein. The authorities which will soon be unleashed lend credence to the assertion that in a situation of self-defense, the attacking party put the defending man in fear, either of death or imminent bodily harm that in the reasonable belief of the defending party, a necessity arose for him to strike the attacker to abate the threat and to save his own life or prevent harm to his person. As Mensah-Bonsu, supra, explains:

“…the imperatives of situation as they appear to a person in a difficult situation may look completely different when the situation is later subjected to objective scrutiny”;

…this strictness is why the defense is difficult to sustain—the succeeding paragraphs dismantle the said difficulty.

To further understand the rationale of self-defense and the circumstances under which that blow, which turned out to be fatal would be deemed necessary and thus, lawful, we take a look at one of the earliest cases; R v. Dudley and Stephens. The two accused killed and ate a cabin boy after they were all shipwrecked. They were rescued four days after killing the boy but evidence suggested that they would all have perished before the rescue if they did not kill and feast on the deceased who was weak and would have likely been the first to die. The court refused the plea of self-defense argued on the grounds of necessity. According to the court, per Lord Coleridge CJ:

“Killing by use of force necessary to preserve one’s own life in ‘self-defense’ was a well-recognized but entirely different case from killing of an innocent person.”

Cardozo J simplifies it as:

“There is no rule of human jettison and so where two or more are faced with a common disaster, there is no right to save the lives of some by killing another.”

With that settled, we now assess the circumstances under which force will be deemed necessary, thus, lawful for self-defense, to the extent of killing.

The requirements to prove justifiable use of force

The onus of proving the use of force—in Section 37 of Act 29 to save one’s own life or the life of another from an attacker is on the accused. And despite its high threshold, it has succeeded in a number of leading authorities—including State v Norman and Palmer v R. The two cases set out the elements of the defense and discuss it at length.

The threat of imminent death or harm

The court, speaking through Mitchell Justice, in Norman, states the first requirement of self-defense to be the threat of imminent bodily harm or death. Where the threat existed but was not imminent, an accused would not be entitled to rely on self-defense for striking the victim. The facts of the Norman were that, the accused was married to the deceased who physically and mentally abused her for years in their marriage. The deceased had threatened on multiple occasions to kill the accused. Being in fear of the threat, the accused resorted to self-help and shot her husband three times while he slept. She was convicted for manslaughter and sentenced to six years. On appeal, the conviction on manslaughter was set aside and a new trial ordered with the instruction that self-defense be submitted to the jury. On further appeal to the Supreme Court, in restoring the decision of the trial court, Mitchell J who spoke for the court, indicated that the threat under which the accused killed her husband was not imminent as he was asleep and in no capacity to attack the accused.

The accused must not instigate a situation to self-defend

The second requirement is that the accused must not be the aggressor or be at a previous fault leading to the confrontation. This provision is illustrated by the Palmer case where the accused and two others stole marijuana from the deceased and on a hot chase, the accused, believing to be in danger from the pursuers, fired at them, killing one. The court rejected the self-defense claim inter alia because, the accused was at fault in the circumstances and did not discharge the ammunition in bona fide belief of being danger.

One contentious issue in the question of self-defense is where an accused in a homicide trial was a provocateur. The deceased, being so provoked, lost self-control and attempted to strike the provocateur with a lethal weapon, but the said provocateur—the accused, launches a preemptive strike which kills the person provoked. Should the benefit of self-defense be available to the provocateur? The authorities suggest so. The American restatement of the law, for instance, says

“A person who provokes another may use force to defend themselves if the person provoked replies the provocation with force. However, unless the force threatened by the person so provoked was deadly, a provocateur cannot use deadly force to resist it.”

The reason a provocateur is not allowed to use lethal force unless the person provoked does so first is that it raises issues of premeditation of the deadly strike, with the provocation of the deceased, only being a means to justify the lethal strike. The fundamental principle governing this is that a person cannot benefit from their own wrongdoing.

Proportionality of force and limits

Proportionality

The third element needed for an accused to prove the harm he caused the deceased as to sustain self-defense is the amount of force used to repel the attack—the general rule being that the force must be proportional to the attack. The memorandum to Act 29 underscores this in the words “the force must always be no more than is reasonably necessary.” The question as regards the amount of force which is reasonably necessary for a victim of an attack to repel his assailant is a question of fact and not of law. This requires the jury to weigh all the evidence adduced and decide if on the facts as presented, the force used in repelling the attack was disproportionate.

In a murder trial where the force is found to be disproportionate, the jury must return a verdict of guilty with no compulsion to consider manslaughter. In determining what amount of force is reasonably necessary to repel an attacker, the requirement is to consider if the person being attacked, reasonably and in good faith, believed the force he used was necessary, even if lethal . It would be wholly unjust for a court to hold a person repelling an attack to strict boundaries of what is reasonably necessary owing to the distinct nature of all cases. In Lord Morris’ words:

“If there has been an attack so that defense is reasonably necessary, it will be recognized that a person defending himself cannot weigh to a nicety the exact measure of his necessary defensive action. If a jury thought that in a moment of unexpected anguish a person attacked had only done what he honestly and instinctively thought was necessary that would be most potent evidence that only reasonable defensive action had been taken.”

This extract from Lord Morris in Palmer, closes the debate on what amount of force should be considered reasonably necessary in the face of imminent danger where one is not an aggressor or at a previous fault.

Limits

Lord Morris explains where the lines of the reaction to the attack should be drawn.

“If an attack is serious so that it puts someone in immediate peril then immediate defensive action may be necessary. If the moment is one of crisis for someone in imminent danger, he may have to avert the danger by some instant reaction. [But] If the attack is all over and no sort of peril remains, then the employment of force may be by way of revenge or punishment or by way of paying off an old score or may be pure aggression …All that is needed is a clear exposition, in relation to the particular facts of the case, of the conception of necessary self-defense. If there has been no attack then clearly there will have been no need for defense.”

In Alhassan v The Republic the Court of Appeal, dismissed the appeal against conviction on murder after the facts showed an intent to kill and the absence of necessary force to end the attack. Per the facts, the deceased and appellant engaged in multiple fights on the day and had been separated by neighbours. On the third fight, the appellant ran into his father’s room, picked a knife, concealed it and came out to meet the deceased and in the course of the fight, stabbed him. He pleaded self-defense. In rejecting the plea, the court, speaking through Abban (Mrs.) J.A. noted that there was a chance to escape the belligerence which the appellant did. He only returned after he was properly armed to strike the deceased in a deadly manner which displays a premeditated intent to kill.

Per Abban (Mrs.) J.A.

“There is no evidence that when the, appellant alleges that he went into the room to pick the knife, the deceased chased him into the room. What prevented him from locking the door when he entered the room?”

The query from Her Ladyship underscores the absence of reasonableness of the force used for self-defense to succeed in this particular case; and the court rightly held that the appeal must fail. From the authorities, it is unmistakable that without a proof of force being reasonably necessary, self-defense cannot be sustained.

As discussed above, at the crux of self-defense is that the threat which was repelled by the defender was imminent, where the attacker has been immobilized therefore, there is no justification to further strike him and the justifiability of the force is limited. The court, per Annan J.A. in Lamptey alias Morocco v The Republic succinctly captures this principle in the words:

“So also where a murderous assailant has been disarmed or disabled in circumstances which show that he is then in no position immediately to resume his criminal purpose or act, then killing cannot be justified.”

The above requirement distinguishes the facts of the killing of Robert Mensah as narrated by the court. The Asante Kotoko goalkeeper still advanced on his killer before he was stabbed. He was not immobilized at the time. The next requirement to succeed on self-defense is equally critical to this paper.

Principle of Duty to Retreat

Fourthly, a controversial issue on the law of justifiable use of force is whether there was any alternative means of reacting to the imminent threat despite the defending party being faultless leading to the attack. Should the accused have opted for a different reaction than striking the deceased? One option which some authorities favour is retreating—running from the scene where possible. How valid is the argument and how does it reflect in legal systems across the world, including ours?

Contrary to what the phrase suggests, the principle of duty to retreat does not impose a duty on a person attacked to retreat at all cost. He is expected to retreat rather than use force, especially lethal, to defend himself. The principle is popular in the United States of America, although, even there, only a handful of the states apply it. The majority favour ‘Stand Your Ground,’ where a person threatened by an attacker can use lethal force to repel the attack, once there is proof they were not the aggressor or provocateur.

The authorities at common law reject the duty to retreat. A leading case which demonstrates this is R v. Bird in which the appellant, struck her ex-boyfriend, wounding him. The facts were that the ex-boyfriend was the aggressor when a fight ensued between the two; he pinned her against a wall and slapped her. She hit him as well, just that there was a glass in her hand which seriously injured him. At trial, the judge directed the jury to return a verdict of not-guilty only if there was evidence she demonstrated an unwillingness to engage in the fight. In allowing her appeal against conviction, Lord Lane CJ noted that although retreating was good evidence that she was unwilling to engage, there was no such duty on a person attacked to retreat. In Palmer, Lord Morris, after a litany of authorities, also rejected the duty to retreat.

Ghanaian authorities reject the duty to retreat as well. In Lamptey alias Morocco, the Court of Appeal ruled:

“If he (the person attacked) found himself in such a situation in an open space, a person may retreat as far as he can go and then turn upon his assailant. However, it cannot be the law that in every case, even in an open space, a victim of a murderous or other serious felonious attack must provide some evidence that he had retreated to some distance.”

The facts were that the deceased and appellant had previous bad blood owing to relations between the appellant’s wife and the deceased. In addition, the deceased regularly rained insults on the appellant, to the point of insulting his mother. One of such instances led to a fight where the appellant testified that the deceased wanted to strike him with a cutlass whereupon he launched a preemptive attack and bludgeoned him with a cudgel he snatched from the deceased. The appellant’s conviction on murder was reduced to manslaughter.

Based on the duty to retreat in Ghanaian law, it is clear that Robert Mensah’s killer was not bound to run away. That notwithstanding, the facts show he even left the scene initially but was followed by the sportsman. Now, the focus turns to the specific provisions in Ghana’s criminal code.

Justifiable Use of Force in Act 29

Part Two, Chapter One of Act 29 extensively deals with justifiable use of force. The relevant portions are highlighted below where necessity is seen as a key component for the defense as Mensah-Bonsu, supra, asserts.

Section 37—Use of Force for Prevention of or Defence against Crime, Etc.

For the prevention of, or for the defence of himself or any other person against any crime…a person may justify any force or harm which is reasonably necessary extending in case of extreme necessity, even to killing.

Section 32—General Limits of Justifiable Force or Harm.

Notwithstanding the existence of any matter of justification for force, force cannot be justified as having been used in pursuance of that matter—

(a) Which is in excess of the limits hereinafter prescribed in the section of this Chapter relating to that matter; or

(b) Which in any case extends beyond the amount and kind of force reasonably necessary for the purpose for which force is permitted to be used.

One leading case which captures the essence of Sections 37 and 32 is Anguyan v. The Republic where the appellant unnecessarily struck the deceased multiple times with a cutlass after a fight between the two. On the evidence adduced, it was apparent that at the time the appellant dealt the deadly blows, the deceased had already been immobilized and posed no further threat to the appellant. The plea of self-defense could, therefore, not be supported. The court, per Forster J.A., in his summing up of the judgment put it simply that

“Even assuming that danger to life was still threatened, was the nature of the wounds inflicted (particularly to the head) reasonably necessary for the purpose for which force is permitted to be used under section 32(b) of the Criminal Code 1960 (Act 29)?”

His Lordship answered in the negative and dismissed the appeal.

The requirement in Section 32 on reasonable force necessary for the purpose for which is was used does not entitle the prosecution or the judge to exclude any class of weapons which the accused used in self-defense (unlike in provocation). Bodua alias Kwata v. The State illustrates this. As per Ollennu JSC:

“The learned [trial] judge misdirected the jury when he told them that what they had to consider was the nature of the instrument used in self-defense…the plain language of the section shows that what may take away the defense is the amount and kind of force used, and not nature and kind of implement used. It cannot be otherwise, because if to ward off a heavy blow aimed at his head with a piece of iron bar, a man in possession of a two-edged dagger so wields the dagger gently so that it only inflicts a superficial wound on the arm of his assailant, his defense of self-defense must succeed.”

As demonstrated by the authorities, only a woefully disproportional force which displays such cruelty or some malicious forethought or launching further attacks on an already immobilized attacker, should disable a person defending himself from the benefit of the complete defense of justifiable use of force.

The similarity between when a reaction to an attack would be deemed self-defense and when the court would interpret it as a reaction from loss of self-control is now apparent. The next section addresses the very thin lines between the two and why the writer avers that the court was wrong to reject Robert Mensah’s plea to succeed on self-defense.

PROVOCATION OR SELF-DEFENSE? –THE FINE LINES

Many scholars agree that there remains many uncertainties on the boundary between murder and manslaughter. The lines between striking another in self-defense and doing same on sufficient provocation from a dangerous assault and battery or threat of imminent harm which causes loss of self-control are as faint as they could get. One variable which has not suffered such atrophy is the requirement for loss of self-control. A person may be justified and completely exonerated if they consciously use as much force as is necessary in the circumstances to defend themselves from an aggressor, including lethal force. However, if the aggressor only succeeded in provoking the defender as to cause them to lose the power of self-control, the crime of murder is only reduced to manslaughter, this is because, it is assumed the loss of self-control clouded the defender’s judgment to less lethal options and the law aims to reduce the instances of people killing out of passion. The loss of self-control is reflected in how passion-filled killers react as seen in the cases above where they strike their attacker multiple times even after they become immobilized.

Where there is no loss of self-control, it is assumed the defender used the lethal force consciously in defending the attack and only its reasonableness in the circumstance would be questioned. In the Palmer case, Lord Morris stressed this in asserting that there is no general rule to convict on manslaughter if the defense of self-defense fails. The verdict should be guilty of murder or not guilty of murder. However, in certain cases where the accused was clearly entitled to use force to defend themselves but the force used was woefully disproportional in the circumstances, an accused’s plea of self-defense will fail and murder may be substituted for manslaughter. The manslaughter element arises because there was loss of self-control in responding to the attack. Cynthia Lee describes this distinction as act reasonableness and emotional reasonableness —explaining that a person full of emotions may be only partially excused in killing their provocateur, if the reaction was reasonable. She continues that in self-defense, only the magnitude of the responding act is questioned as there is a prima facie belief that a person acting in self-defense of an imminent attack should defend themselves with necessary counterforce.

Act 29 illustrates this distinction as regards self-control in Section 37 and Section 52 (b).

Section 37, which says for the prevention of, or for the defence of himself or any other person against any crime…a person may justify any force or harm which is reasonably necessary extending in case of extreme necessity, even to killing—demonstrates the requirement to use necessary force in the circumstances and its proportionality while

Section 52 (b) –which reads: the defense of provocation may be available to an accused if he was justified in causing some harm to the other person, and, in causing harm in excess of the harm which he was justified in causing, he acted from such terror of immediate death or grievous harm as in fact deprived him for the time being of the power of self-control—demonstrates the requirement for the accused, or the jury to find loss of self-control for the defense to succeed.

Secondly, while an accused in a homicide trial relying on self-defense must prove that it was necessary to use lethal force and that the force used was reasonable or proportionate in the circumstance, an accused pleading provocation need not prove that their action was necessary; all they need to prove is that the force they used was not unreasonable. In the Alhassan case, the court dismissed the appeal because it found no necessity for the appellant to return from his room just to stab the deceased.

Finally, Lamptey alias Morocco stresses the distinction between the two defenses; stating that necessity was needed to sustain a plea of self-defense while sufficient provocation supports the defense of provocation. In his assessment of the self-defense plea, Annan J.A. indicated that:

“What amounts to extreme necessity has not been defined in the [Act] and this must have been on purpose, and no useful purpose would be served by attempting a definition. What maybe done is to give instances of what may amount to extreme necessity, and care must be taken by the judge not to give the impression to a jury that circumstances of extreme necessity could only arise in the instances enumerated by him.”

He further summarized the core of the defense as thus:

“The essence of self-defense is the right of a man to protect himself against any criminal attack on his person. A man has the right to the preservation of his whole person or any part thereof. Where that right is immediately invaded or threatened by criminal conduct he is entitled to repel the invasion or nullify the threat.”

On the defense of provocation, Annan J.A. had this to say on the circumstance of the Lamptey case:

“That was an unlawful assault and battery committed against the appellant by the deceased who was the aggressor. That unlawful assault and battery was of a very violent nature and was inflicted with a heavy instrument — the same instrument which was later used by the appellant on the deceased. Again apart from the violence of that unlawful attack on the appellant, there were words and other circumstances of insult accompanying that act. The deceased had made a rude exclamation about the mother of the appellant and one which a good many people may well find difficult to let pass. It seems reasonably clear that in the particular circumstances of this case, the appellant was greatly provoked by the initial conduct of the deceased. The verdict of guilty of murder, therefore, cannot be supported.”

The two defenses also differ in reference to the weapon used in striking the deceased. Whereas self-defense does not consider the weapon used, Act 29 expressly mentions that the weapon used could disable the accused from relying on the defense of extreme provocation.

In summary, for self-defense, loss of self-control is replaced with proportionality with which the accused repelled the attack, and as mentioned, that balance is determined by the reasonable belief of the man defending himself in the moment and not with the benefit of hindsight. Extreme provocation simply rides on the assumption that the deceased undermined the accused’s power of self-control, causing the latter not to think through his reaction which the authorities term the accused was not “a master of his mind.” In self-defense, the accused, acted voluntarily with support of all his faculties.

How these laws reflect in Robert Mensah’s killing.

THE ROBERT MENSAH (MELFA) CASE IN FOCUS

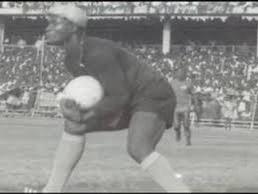

The facts of Melfa, the analysis of which the above exposition will provide context are simple and not at all difficult to grasp. Robert Mensah, described by Sowah J.A., as an international football star was at a drinking bar with some friends when a fight developed between him and one of his friends. The appellant, who was also at the bar—on a different table, did what any reasonable man would do and tried to separate them but the deceased turned on the appellant and beat him up and threw him into a fence. The appellant was advised to retreat and leave, which he did. Shortly after, the deceased followed him and resumed the attack on him. He picked up a broken bottle and warned the deceased to stop the attack but the deceased still advanced, whereupon, in the face of the imminent threat, he stabbed the attacker. Robert Mensah died in the hospital from the wound.

The trial judge indicated the stabbing was a crime of violence, for which he imposed eight years for manslaughter and the Court of Appeal reduced the sentence to four years after dismissing the appeal against conviction. To this, Sowah J.A. responded “each crime of violence should be considered on its own merits;” I agree. However, was a crime committed by the appellant in the violent episode? The discussion to this point will aid in drawing a conclusion. In the introduction, the paper mentions the formula used to arrive at criminal liability which is Mens Rea plus the Actus Reus and the absence of a valid defense—which negates the Mens Rea or intent, in this case. A complete defense will thus, discharge an accused of liability. In applying the authorities discussed, the first question is did the appellant lose the power of self-control as to rely on provocation? The answer is in the negative. As provided for in Section 53 and applied in Lamptey, assault and battery must be of a kind, in respect of its violence or by reason of accompanying words, gestures, insults or other circumstance, actually cause the accused to so impassioned, thus losing the power of self-control. The facts in Melfa suggest no loss of self-control—especially where the appellant took the pain to warn the deceased instead of just pouncing in rage as the cases discussed above illustrate.

Section 52 (b) supra, which is another matter of partial excuse also does not apply here. It provides that the accused “was justified in causing some harm to the other person, and, in causing harm in excess of the harm which he was justified in causing, he acted from such terror of immediate death or grievous harm as in fact deprived him for the time being of the power of self-control”

The Anguyan case has already demonstrated what constitutes excess force. That is where the attacker was already immobilized and the defender still struck him. In Melfa, the only time the appellant struck the deceased as the judgment shows is when the deceased still advanced—posing the imminent threat, the harm was therefore not in excess.

Section 52 (b) also requires that the threat deprives the accused of the power of self-control. Anguyan, again demonstrates what actions a court should assess to determine loss of self-control. In the case, it is stated clearly that the appellant struck the deceased multiple times, even after he became incapacitated—confirming he was momentarily not a master of his mind. In Kontor, there is an immediate expression of remorse from the appellant after he struck the deceased, also affirming a brief moment of losing the power of self-control. None of these are present in Melfa. The conviction on manslaughter which the Court of Appeal upheld can therefore, not stand and should have been quashed; for the decision was against the weight of evidence. As explained by the Palmer case, there is no general rule that where the plea of self-defense fails, manslaughter be substituted.

Where the elements of provocation fail as evident in the preceding paragraph, only two options remain, guilty of murder or not guilty of murder. The requirements to succeed on self-defense, having been discussed at length, will now be applied to the facts of the case under review.

Firstly, does the appellant have a right to self-defense? That is an affirmative. Was the threat imminent as required by Act 29, Norman, Anguyan, Palmer and the other authorities? Yes, as the deceased was not immobilized and still advanced on the retreating appellant. Was there a duty on the appellant to run away from the scene? The persuasive foreign authorities and binding home authorities lead us to answer this in the negative. Lord Lane CJ in the Bird case minces no words when he says there is no duty on a person being attacked to retreat. Lord Morris approves this in Palmer and Annan J.A., in Lamptey alias Morocco stresses the point which is repeated here that

“It cannot be the law that in every case, even in an open space, a victim of a murderous or other serious felonious attack must provide some evidence that he had retreated to some distance.”

Lord Morris (Justice)

And even if there court required some proof of retreat in this specific circumstance, the appellant did retreat from the club when asked to do so; only to be pursued by the deceased. Lastly, the accused in a self-defense plea, must prove that in the particular circumstance, they did not use unreasonably disproportionate force. If there is any doubt as to the proportionality of the force, the fundamental principle is that the doubt must go in favour of the accused. What is proportional force always depends on the circumstances of the case; there is no general rule except in the circumstances, it should not be disproportionate.

Should the appellant have used a weapon or engaged the deceased in a fist fight to defend himself? Sowah J.A. describes the deceased as a man of violent temper; he is a sportsman and is physically fit as all active sportsmen are—would a reasonable man engage a physically fit man of “violent temper” in a fist fight when he is not the aggressor? It does not appear so. More so, In the Alhassan case, the appellant ran into his father’s room to retrieve a knife before coming out to continue the fight which was evidence that he could have locked the door and disengaged the fight as Abban (Mrs.) J.A noted.

In the instant matter, as Sowah J.A. recounted, the appellant merely picked up the broken bottle with which he stabbed the deceased and being around a drinking bar, broken bottles lying around are not out of the ordinary—there is no mention of the appellant picking the broken bottle before exiting the club which would suggest premeditation as Alhassan illustrates. And as Bodua alias Kwata explains, what might take away the plea of self-defense, is the amount of force used and not the nature of the weapon. The question of the broken bottle is, thus, defeated.

On the manner in which it was used and whether the appellant could have struck a less delicate part of the deceased’s body, the relevance of Lord Morris in Palmer is brought to fore.

The judge says:

“It will be recognized that a person defending himself cannot weigh to a nicety the exact measure of his necessary defensive action. If…a person attacked had only done what he honestly and instinctively thought was necessary that would be most potent evidence that only reasonable defensive action had been taken.”

Lord Morris (Justice)

Professor Lee, in her article supra, agrees. She argues that the test of proportionality of the defensive action is in the reasonable belief of the person so defending himself against an unprovoked aggressor, to which the present writer concurs.

The basic human instinct is to survive and not to navigate the fine grains of legalese. How just then, would it be, for a court to expect an adrenaline-filled man, seeking only to survive an attack, to pause and consider the niceties of what a jury would consider proportionate before fending off the attack? Ridiculously unjust! In the present circumstances, therefore, it is reasonable to conclude, with all the authorities applied to the facts, that the force applied was reasonable and proportional; and if at all, any doubt remains in the mind of the court, which this writer disputes, the principle is that the doubt must lead the court to acquit. From the foregoing, this writer asserts that Sowah’s Court, respectfully, erred in dismissing Melfa’s appeal.

CONCLUSION

It is good law that no legal system permits impulsive homicide on the least provocation. Be that as it may, the law cannot as well stymie a non-belligerent party in the face of imminent bodily harm or death. All life is sacrosanct but if one person puts another in fear of losing theirs or in fear of being so harmed as to lose the goodies of a fully functioning body, no impediments placed on the defending party’s right to resist such threats should be justified as the list of authorities at odds with Melfa demonstrate.

A proposed accurate direction which should be given to juries and which should guide the courts, garnered from the list of authorities appraised for this paper should be or substantially similar to: where the facts show that the defending party had enough time to retreat, and did so but then turns around to re-engage the initial attacker, this time with a lethal weapon, it is enough proof of premeditation and both defenses of extreme provocation and self-defense must fail. Where the facts show that the defending party further struck the attacker after the latter had become immobilized, it is evidence of excessive force for revenge and not self-defense and both defenses must fail. Where the evidence shows that on persistent attacks, the defending man dealt a grievous blow on an aggressor, the jury should assess the surrounding circumstances to conclude if he did so upon losing control of his faculties, if so, provocation must succeed, unless where it was not a single strike and further blows were dealt after the attacker had become immobilized or the weapon used displayed some forethought or cruelty, then both defenses must fail. Finally, where the facts show the defending party only struck the aggressor while the attack was still imminent, that is enough evidence that only reasonable and proportionate force was used and self-defense must succeed. Melfa falls within the last scenario.

The so-called social contract notwithstanding, the great libertarian philosopher, John Stuart Mill wrote: “each is a proper guardian of his own health, whether bodily or mental or spiritual.” The right to self-defense is, therefore, fundamental and inalienable; this is the writer’s position.

POSTSCRIPT

—

First of all, it is without doubt that the killing of Robert Mensah pained the nation. Football, undoubtedly, is a passion of this nation and Robert Mensah’s prowess were not in doubt. The Black Stars could have gone places with him in the posts. The sentiments of the nation was high and the people cried for vengeance against his killer. It is, therefore, understandable, the difficult situation in which their Lordships found themselves. Were they just going to let the killer off the hook? Would Ghanaians have understood or would they say well, some money probably exchanged hands? These sentiments, notwithstanding, we should always be guided by the dictum of Edusei J in Allasan Kotokoli v. Moro Hausa:

“Sentiments must not have a place in the administration of the law otherwise the growth of the principles of the law as enunciated in courts’ decisions would be stifled and jurisprudence would be worse for it.”

Secondly, the two-page decision fails to mention the legal arguments advanced in favour of the appellant. The direction given to the jury by the trial judge is also not referenced—which does a disservice to anyone seeking to critique their Lordships’ conclusion. However, the opening lines of the decision which read:

“We have listened carefully to the able submission made by Mr. Okyere-Darkoh in his attack on the conviction of the appellant…” supports an assumption that self-defense was argued. A thorough discussion on those arguments could have aided later generations to appraise the judgment better.

—End—

CLICK HERE TO DOWNLOAD THE PAPER. READ WHEN THE SPEAKER IS NOT A SPEAKER HERE

Source - Oswald Azumah

1 Comment

Wisdom kofi Xexemekpe

3 years agoAs a lay man, this disposition has brought a lot of understanding as to what the law says in this type of situations. The writer has explained vividly with examples of other similar situations that made the disposition fun to read and educative. This will go along to help me know what to do if I find myself or loved ones in this type is situations. I can not but agree with the writer on this one. The Appellant should have walked free.